Shipwreck victims cast adrift for weeks or months exhibit a resilience that serves as a model to weather any extended crisis

The following written content from Luc-Christophe Guillerm

On April 14, 2002, while routinely patrolling the Indian Ocean, a French Navy vessel spotted a dinghy with two passengers onboard. They had been drifting for 20 days. After being shipwrecked, they had escaped in a seven-meter-long lifeboat. They survived exposure, the blazing sun and a failed motor by drinking rainwater and eating bream that they fished from the sea with harpoons. After drifting 750 kilometers, the passengers’ survival seemed miraculous.

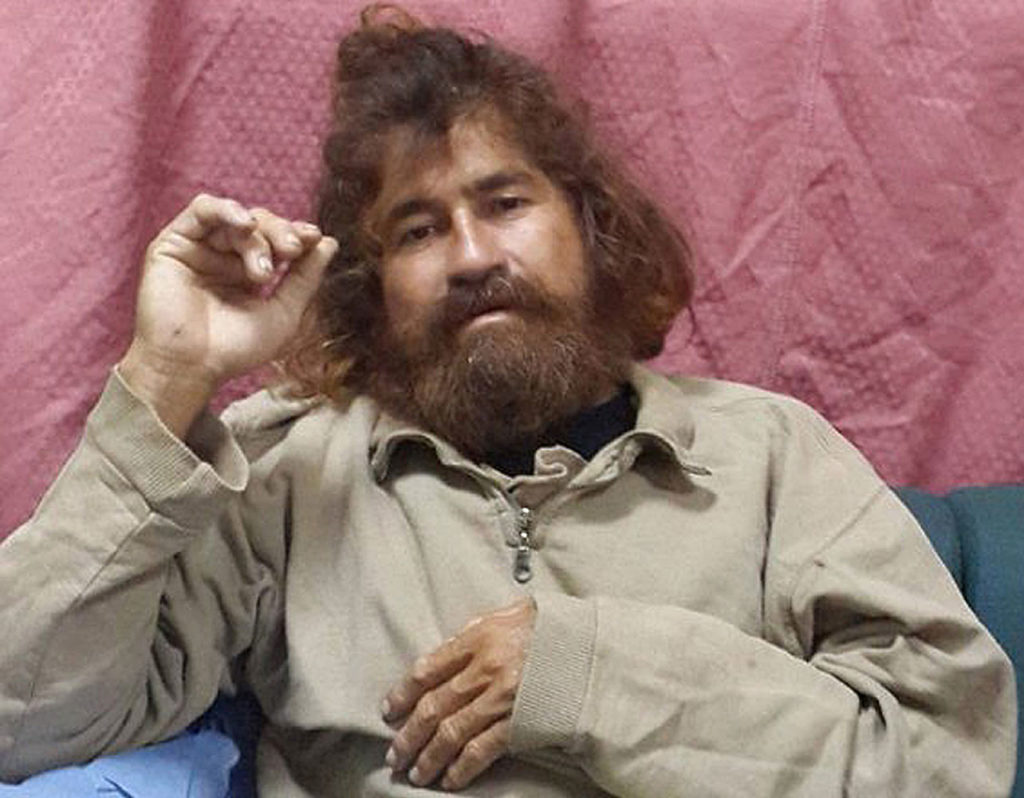

Every year, stories emerge of people who manage to endure weeks or months onboard a simple craft. Some of these accounts are legendary, such as a case that was immortalized by French artist Théodore Géricault in his painting The Raft of the Medusa. After a French Frigate called the Medusa ran aground on a sandbank off of what is now Mauritania in 1816, nearly 150 survivors crammed onto an improvised raft. Only 10 survived. The present record for endurance goes to Salvadoran fisherman José Salvador Alvarenga, whose boat was swept offshore by high winds and a storm before running out of fuel. Between mid-November 2012 and late January 2014—a period of 438 days and a distance of 9,000 kilometers—Alvarenga drifted across the Pacific. For the first four months, he was accompanied by a co-worker, who later died.

Some shipwreck survivors leave eyewitness accounts, making it possible to explore a fundamental question: Aside from the material requirements for staying alive, how do survivors psychologically cope with such an ordeal?

THE TRAUMA OF THE CASTAWAY

Being shipwrecked is one of the most calamitous experiences that can happen to a human. The initial shock is severe: victims of a shipwreck see their boat sink, feel the icy contact with the ocean and must quickly find a solution. Within a few minutes, they may find themselves in a crude but more or less well-equipped lifeboat—for an indeterminate period of time. They are often alone, lost in the vastness of the ocean, tossed by waves on all sides that obliterate the horizon. When victims are accompanied by other people, they suffer less from loneliness, but the situation comes at the cost of privacy. They cannot be alone even for a second. In an instant, a shipwreck upends all points of reference, whether material, emotional, social or sensory. The feeling is one of awful separation, accompanied by acute anxiety, and sometimes panic, commensurate with a total breakdown of the familiar environment.

Once the acute phase of the shipwreck has passed, great uncertainty sets in. For people not used to the sea, living conditions are almost impossible to imagine: the looming risk of death; the confinement; the absolute and unrelieved isolation; the total lack of comfort; the appalling hygiene; the constant humidity; the attack of the salt and sun on the skin; the freezing cold in some cases; the sleeplessness; the seasickness; and the muscle pains from awkward positions—not to mention the lack of water and food. The list is endless. Extreme fatigue follows quickly, accentuated by the dramatic circumstances of the shipwreck.

LIFE OF THE CASTAWAY

Psychologically, shipwreck victims go through an extremely painful experience. They constantly feel a dull anxiety, which at times turns into terror, depending on unforeseen events, such as the appearance of sharks, the deflation or capsizing of the lifeboat, the onset of disease and the death of a companion.

The main risk at the time of the shipwreck is panic. Eventually, however, it evolves into passivity—the castaway’s worst enemy. Passivity is naturally linked to the monotony of life adrift but also to hopelessness, which can set in rapidly and have fatal consequences. After a few weeks, some survivors become indifferent to everything and basically let themselves go. The case of the Marie-Jeanne, a motor launch that broke down off the Seychelles in 1953, is illustrative. The 10 passengers who remained onboard abandoned any attempt to feed themselves or even to fish. They simply waited. On the 74th day, when an Italian tanker found them, only two young men were left alive, collapsed in a corner.

Another psychological feature observed in shipwreck survivors is the profound transformation of their connection to reality, which includes an altered perception of time and the blurring of spatial boundaries. An impression of having always lived at sea and being outside of time rapidly takes hold as the present expands, blotting out past and future. “Day followed day without making any impact on our minds,” wrote Maurice Bailey of the 119 days he and his wife Maralyn spent cast away on a life raft in the Pacific in 1973 in their book Staying Alive! On the 104th day, he wrote, “it appeared as though we knew no other life. I had stopped dreaming about our life before or after this misadventure.”

Disturbances in the perception of reality often result, including illusions and sometimes hallucinations. Various factors may contribute, such as constantly disturbed sleep, metabolic disorders, fatigue and dehydration, as well as a defense against anxiety and a spiritual identification with nature. This identification may often be enhanced by the experience of an “oceanic feeling,” the sensation of being at one with the universe, which was notably described by Sigmund Freud in his 1929 book Civilization and Its Discontents. Sometimes delusional episodes occur, as in the case of the Medusa.

REGAINING CONTROL

After an initial period of despair and hopelessness, the shipwrecked have no choice but to pull themselves together. Many of them pursue positive and active strategies, although these may be interspersed with phases of deep despondency. The first step often consists of taking stock of the situation and planning what to do next: inventorying food and survival equipment, stowing them in the lifeboat and estimating how long it will be before help comes. This step is essential in the fight against complacency and anxiety in order to develop a sense of regaining control.

In the face of danger, castaways’ psychological reaction—especially stress – depends on how they assess their ability to control events and to cope with the situation. “Perceived control” is a subjective ability that varies from one individual to another, but it is also based on objective considerations, such as available materials and food. Consequently, several factors are likely to favor it, such as information about the situation, knowledge of the rules of survival and other castaway stories, and, in particular, rejection of inactivity. Any number of activities may thus restore the feeling of control: collecting rainwater, improving one’s fishing technique, making a fire to cook an albatross or catching a turtle. After her shipwreck off the Solomon Islands in 1990, French sailor Claudine Paré-Lescure escaped in an inflatable dinghy and used the paddles to build a makeshift mast. Although her boat was hard to maneuver, the simple fact of moving forward had a salutary effect on her mood.

Belief in one’s ability to control events and feeling involved in activities are two of the three characteristics of stress resistance proposed in a 1979 study by psychologist Suzanne Ouellette (at the time Suzanne Kobasa), who also employed the term “hardiness.” The third characteristic is anticipating change in a positive way. “Among persons under stress, those who view change as a challenge will remain healthier than those who view it as a threat,” Kobasa wrote. “Persons who feel positively about change are catalysts in their environment and are well practiced at responding to the unexpected.” Indeed, some shipwreck survivors are sailors who are used to competition (such as the Vendée Globe, a major sailing race around the world) and generally manage to see an opportunity to progress with each new challenge they encounter—whether they are dealing with a technological innovation or a hardware glitch.

Aside from the feeling of regaining control, the different activities that set a rhythm for the day have another advantage. They help combat the unbearable expansion of the present by creating a segmented perception of time focused on the current experience. Bathing, having breakfast, fishing, tidying up, eating lunch, taking a nap, playing games, sleeping. Establishing these routines is not easy because it means disregarding the condition of being shipwrecked. But it is a healthy reflex.

A case in point is the Robertson family, whose schooner was attacked by killer whales in 1972 and who survived for 38 days onboard an inflatable raft and a fiberglass dinghy. The family divided up the tasks. The father, Dougal Robertson, prepared turtle meat and fished. His wife Lyn Robertson took care of the “house” and the children. She encouraged them to keep up their personal hygiene, exercise, write to friends and draw on a piece of sailcloth. In the evening she sang them Johannes Brahms’s “Lullaby” to help them sleep. The Robertsons also invented games, recalled their travels and discussed delicious meals that they would make. These activities kept them busy and distracted their attention from the perils of their situation. More important, daily routines provided structure and the semblance of an organized life, averting the anxiety that would have resulted from jettisoning all the customary rules.

Keeping busy, however, is not the only way to regulate the day. Anything that breaks the monotony is useful, observed Xavier Maniguet, a physician and a survival specialist, in his book Survival: How to Prevail in Hostile Environments. “To cope with the apparent nothingness, [the castaway] must structure his landscape,” Maniguet wrote. “Clouds and waves, dawn and dusk, storms and swells, marine and avian life—everything must become an event, an excuse for reflection, an opportunity to act, any and all reasons to break a desperately repetitive cycle.”

IMAGINATION TO THE RESCUE

Nevertheless, the length of time spent adrift and the harshness of the material conditions cause substantial suffering. And resorting to activities or events does not suffice. Another dimension emerges from the accounts of people who have survived extreme situations, whether at sea or in the mountains or even under imprisonment and torture—namely, an astonishing ability to use the imagination and an inner space. In this way, castaways compensate for their hostile environment with thoughts and reveries that carry them to other places or remind them of their loved ones.

Mental imagery appears to be very effective for regulating emotions and escaping. There is no need to fantasize about extraordinary adventures. Reality is already sufficiently out of the ordinary, and the humdrum does the trick. Frequent themes are food, particularly meals and menu planning. The late British yachtsman Tony Bullimore, who was shipwrecked during the 1996–1997 Vendée Globe, recounted one of his daydreams in his book Saved: The Extraordinary Tale of Survival and Rescue in the Southern Ocean. “I take the car and drive down Ashley Road in St Paul’s [in England] to meet Ronald, a friend of mine, at the Cambridge for a few drinks,” he wrote.The simple of fact of thinking about family and friends increases the motivation to survive. Sailor Steven Callahan, who lived for two and a half months in a lifeboat in 1982, explained in his book Adrift: Seventy-Six Days Lost at Sea that he “[lowered] the drawbridge to childhood memories” and, as he visualized the rooms of his early years, saw himself back with his toy soldiers. The boundary between revery and hallucination may blur. Some shipwreck survivors report visions of submarines delivering fresh bread and couscous, friends whipping up chocolate mousse in their kitchen or simply fresh water.

At other times, people manage to survive psychologically by planning projects. Any idea, even a utopian one, will do: building a boat or a house, gardening or testing out recipes. In a way, thinking about the future is to believe in survival. The Robertsons often imagined what they would do once they returned home, for example—the cat they would get and the restaurant they would open. Read more from Scientific America