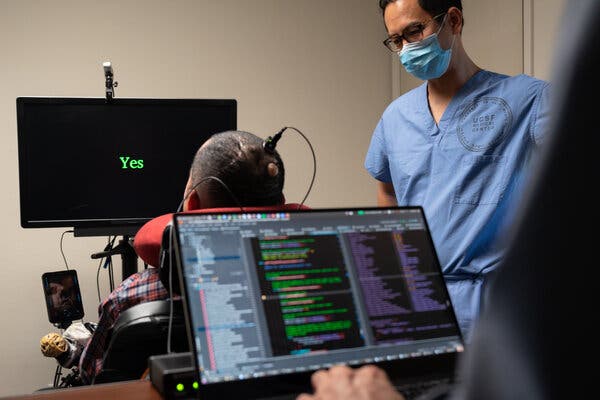

Electrodes implanted in the man’s brain can transmit signals to a computer and display his thoughts.

The following written content from Pam Belluck

He has not been able to speak since 2003, when he was paralyzed at age 20 by a severe stroke after a terrible car crash.

Now, in a scientific milestone, researchers have tapped into the speech areas of his brain — allowing him to produce comprehensible words and sentences simply by trying to say them. When the man, known by his nickname, Pancho, tries to speak, electrodes implanted in his brain transmit signals to a computer that displays them on the screen.

His first recognizable sentence, researchers said, was, “My family is outside.”

The achievement, published on Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, could eventually help many patients with conditions that steal their ability to talk.

“This is farther than we’ve ever imagined we could go,” said Melanie Fried-Oken, a professor of neurology and pediatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, who was not involved in the project.

Three years ago, when Pancho, now 38, agreed to work with neuroscience researchers, they were unsure if his brain had even retained the mechanisms for speech.

“That part of his brain might have been dormant, and we just didn’t know if it would ever really wake up in order for him to speak again,” said Dr. Edward Chang, chairman of neurological surgery at University of California, San Francisco, who led the research.

The team implanted a rectangular sheet of 128 electrodes, designed to detect signals from speech-related sensory and motor processes linked to the mouth, lips, jaw, tongue and larynx. In 50 sessions over 81 weeks, they connected the implant to a computer by a cable attached to a port in Pancho’s head, and asked him to try to say words from a list of 50 common ones he helped suggest, including “hungry,” “music” and “computer.”

As he did, electrodes transmitted signals through a form of artificial intelligence that tried to recognize the intended words.

“Our system translates the brain activity that would have normally controlled his vocal tract directly into words and sentences,” said David Moses, a postdoctoral engineer who developed the system with Sean Metzger and Jessie R. Liu, graduate students. The three are lead authors of the study.

Pancho (who asked to be identified only by his nickname to protect his privacy) also tried to say the 50 words in 50 distinct sentences like “My nurse is right outside” and “Bring my glasses, please” and in response to questions like “How are you today?”

His answer, displayed onscreen: “I am very good.”

In nearly half of the 9,000 times Pancho tried to say single words, the algorithm got it right. When he tried saying sentences written on the screen, it did even better.

By funneling algorithm results through a kind of autocorrect language-prediction system, the computer correctly recognized individual words in the sentences nearly three-quarters of the time and perfectly decoded entire sentences more than half the time.

“To prove that you can decipher speech from the electrical signals in the speech motor area of your brain is groundbreaking,” said Dr. Fried-Oken, whose own research involves trying to detect signals using electrodes in a cap placed on the head, not implanted.

After a recent session, observed by The New York Times, Pancho, wearing a black fedora over a white knit hat to cover the port, smiled and tilted his head slightly with the limited movement he has. In bursts of gravelly sound, he demonstrated a sentence composed of words in the study: “No, I am not thirsty.”

In interviews over several weeks for this article, he communicated through email exchanges using a head-controlled mouse to painstakingly type key-by-key, the method he usually relies on.

The brain implant’s recognition of his spoken words is “a life-changing experience,” he said.

“I just want to, I don’t know, get something good, because I always was told by doctors that I had 0 chance to get better,” Pancho typed during a video chat from the Northern California nursing home where he lives.

Later, he emailed: “Not to be able to communicate with anyone, to have a normal conversation and express yourself in any way, it’s devastating, very hard to live with.”

During research sessions with the electrodes, he wrote, “It’s very much like getting a second chance to talk again.”

Pancho was a healthy field worker in California’s vineyards until a car crash after a soccer game one summer Sunday, he said. After surgery for serious damage to his stomach, he was discharged from the hospital, walking, talking and thinking he was on the road to recovery.

But the next morning, he was “throwing up and unable to hold myself up,” he wrote. Doctors said he experienced a brainstem stroke, apparently caused by a post-surgery blood clot.

In interviews over several weeks for this article, he communicated through email exchanges using a head-controlled mouse to painstakingly type key-by-key, the method he usually relies on.

The brain implant’s recognition of his spoken words is “a life-changing experience,” he said.

“I just want to, I don’t know, get something good, because I always was told by doctors that I had 0 chance to get better,” Pancho typed during a video chat from the Northern California nursing home where he lives.

Later, he emailed: “Not to be able to communicate with anyone, to have a normal conversation and express yourself in any way, it’s devastating, very hard to live with.”

During research sessions with the electrodes, he wrote, “It’s very much like getting a second chance to talk again.”

Pancho was a healthy field worker in California’s vineyards until a car crash after a soccer game one summer Sunday, he said. After surgery for serious damage to his stomach, he was discharged from the hospital, walking, talking and thinking he was on the road to recovery.

But the next morning, he was “throwing up and unable to hold myself up,” he wrote. Doctors said he experienced a brainstem stroke, apparently caused by a post-surgery blood clot. Read more from NYT