A great mystery older than Stonehenge–

Reshaping previous ideas on the story of civilization, Gobekli Tepe in Turkey was built by a prehistoric people 6,000 years before Stonehenge.

The following written content by Andrew Curry

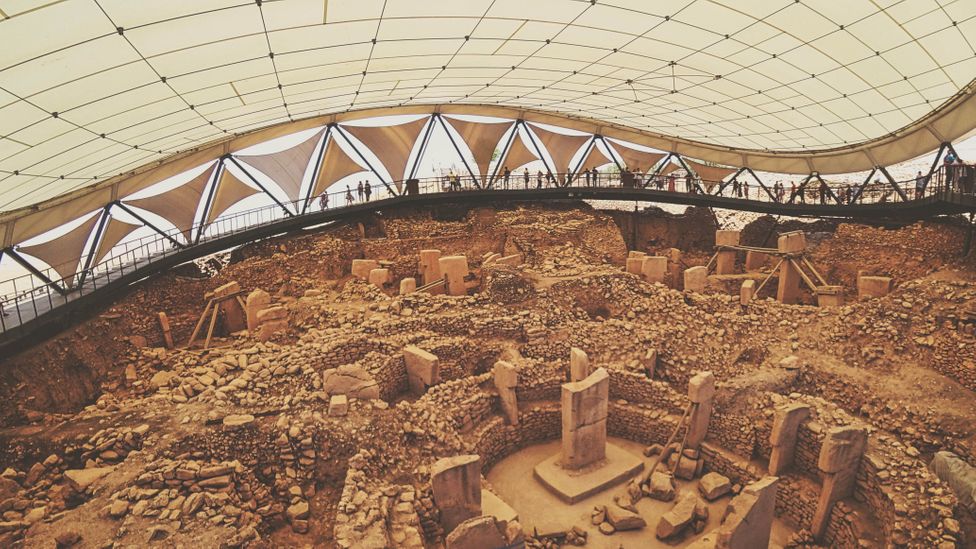

Situated in modern-day Turkey, Gobekli Tepe is one of the most important archaeological sites in the world (Credit: Michele Burgess/Alamy)

When German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt first began excavating on a Turkish mountaintop 25 years ago, he was convinced the buildings he uncovered were unusual, even unique.

Atop a limestone plateau near Urfa called Gobekli Tepe, Turkish for “Belly Hill”, Schmidt discovered more than 20 circular stone enclosures. The largest was 20m across, a circle of stone with two elaborately carved pillars 5.5m tall at its centre. The carved stone pillars – eerie, stylised human figures with folded hands and fox-pelt belts – weighed up to 10 tons. Carving and erecting them must have been a tremendous technical challenge for people who hadn’t yet domesticated animals or invented pottery, let alone metal tools. The structures were 11,000 years old, or more, making them humanity’s oldest known monumental structures, built not for shelter but for some other purpose.

After a decade of work, Schmidt reached a remarkable conclusion. When I visited his dig house in Urfa’s old town in 2007, Schmidt – then working for the German Archaeological Institute – told me Gobekli Tepe could help rewrite the story of civilisation by explaining the reason humans started farming and began living in permanent settlements.

The stone tools and other evidence Schmidt and his team found at the site showed that the circular enclosures had been built by hunter-gatherers, living off the land the way humans had since before the last Ice Age. Tens of thousands of animal bones that were uncovered were from wild species, and there was no evidence of domesticated grains or other plants.

Schmidt thought these hunter-gatherers had come together 11,500 years ago to carve Gobekli Tepe’s T-shaped pillars with stone tools, using the limestone bedrock of the hill beneath their feet as a quarry.

Carving and moving the pillars would have been a tremendous task, but perhaps not as difficult as it seems at first glance. The pillars are carved from the natural limestone layers of the hill’s bedrock. Limestone is soft enough to work with the flint or even wood tools available at the time, given practice and patience. And because the hill’s limestone formations were horizontal layers between 0.6m and 1.5m thick, archaeologists working at the site believe ancient builders just had to cut away the excess from the sides, rather than from underneath as well. Once a pillar was carved out, they then shifted it a few hundred metres across the hilltop, using rope, log beams and ample manpower. Read more from BBC.