Studying the 1000 year old engineering marvels of India may provide the solution to water shortage issues

The following written content from Feza Tabassum Azmi

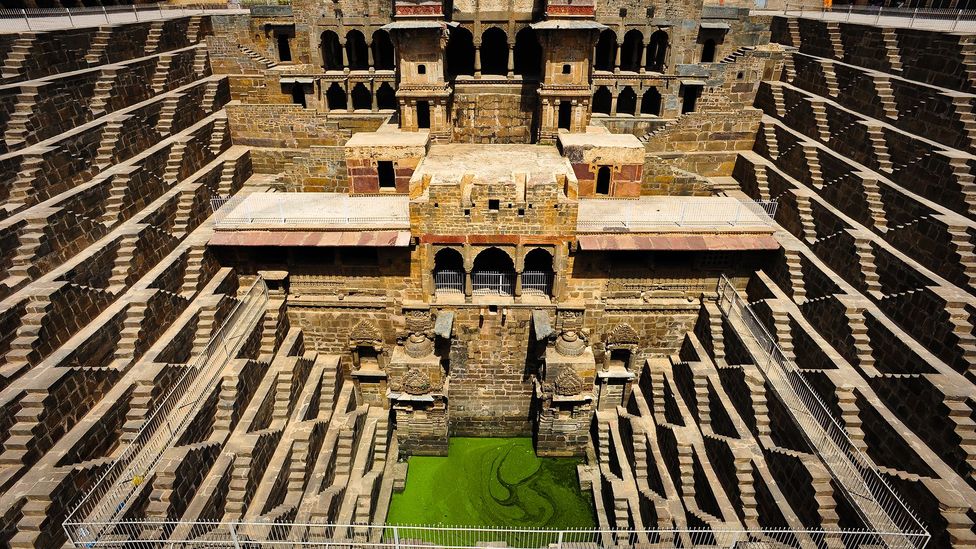

Huge architectural gems built deep into the Earth like inverted fortresses are scattered around India – and restoring them may be a solution to help the country’s parched communities.

An exquisitely carved maze of 3,500 steps, arranged in perfect symmetry, descends with geometrical precision to reach a well. Criss-crossed steps encircle the water on three sides, while the fourth side is adorned by a pavilion with embellished galleries and balconies. Built by Rajput ruler Raja Chanda during the 8th-9th Century, Chand Bawri in Abhaneri, Rajasthan, is India’s largest and deepest stepwell. Extending down 13 floors, or 100ft (30m), into the ground, it is a captivating example of inverted architecture.

Plunging into the earth, stepwells like Chand Bawri were built in drought-prone regions of India to provide water all year round, ensuring communities had access to vital water storage and irrigation systems.

Centuries of natural decay and neglect, however, have pushed these structures into oblivion. Dating back more than 1,000 years, the stepwells (baoli, bawri, or vav) are crumbling into obscurity. Their value has gone largely unnoticed by town planners as modern running water systems eclipsed their importance. Many stepwells are in shambles or have caved in. Some have disappeared completely.

But in recent years, many of these ancient edifices are being restored to help tackle India’s acute water problem. The country is currently undergoing the worst water crisis in its history, according to a recent government report. There are hopes that the ancient technology of the stepwells might offer a solution.

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), India is the world’s largest extractor of groundwater. The groundwater level in India is estimated to have declined by 61% between 2007 and 2017. The depletion of this vital resource not only threatens people s access to drinking water but also food security by resulting in a reduction in food crops by up to 68% in severely-hit regions.

India receives about 400 million hectare metres of rain annually, but nearly 70% of surface water is unfit for human consumption due to pollution. India is ranked 120th out of 122 countries in the water quality index. An estimated 200,000 people die every year due to inadequate water.

The government emphasises the need to use India’s historic water management systems for solutions to these problems. States can leverage new technologies to modify traditional water systems for local requirements. In a nation where 600 million people – around half the population – face severe water shortages daily, traditional water-harvesting solutions are a harbinger of hope. “With India’s water table rapidly declining, stepwells can help refill ground aquifers and harvest runoffs. In three months during the rainy season, millions of litres of water can be collected,” says Ratish Nanda, a conservation architect and projects’ director at the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, an organisation leading restoration efforts.

In 2018, the government of Rajasthan, one of the most water-scarce regions in the world, drew up a comprehensive framework, with technical assistance from the World Bank, for restoration of the stepwells, including Chand Bawri.

“The Rajasthan government, through its flagship program Mukhyamantri Jal Swavalamban Abhiyan, has taken initiatives to make villages self-sufficient in water by reviving the non-functional rainwater harvesting structures,” says Mohit Dhingra, who teaches at Jindal School of Art and Architecture in Sonepat, India, and is associated with conservation projects in India.

“India has a comprehensive water eco-system, but most of the traditional water bodies have become defunct. Reviving the stepwells will enable people to reclaim their traditional resources and spaces of community life. With the holding capacity that stepwells like Chand Bawri have, a great burden of water scarcity can be mitigated,” he says.

Bansi Devi, who rears cattle for a living in Rajasthan, has already noticed a change. “We had to walk for hours searching for water,” she says. “Now I can use water from the revived baoli in my village for our domestic use and also for feeding and washing the cattle.”

In Jodhpur city, the Toorji stepwell was restored after a team spent several months pumping out stagnant water. Decades of toxic water had turned the red sandstone white, with half an inch of thick crust covering much of the surface. Sand-blasting was carried out to clean the thick white crust of deposits on the wall, at a cost of about 1.5 million Indian rupees (£14,784). About 28 million litres (6.2 million gallons) of water per day is supplied to the city by other recently cleaned stepwells for irrigation and domestic purposes. Read more from BBC