Snowflakes-

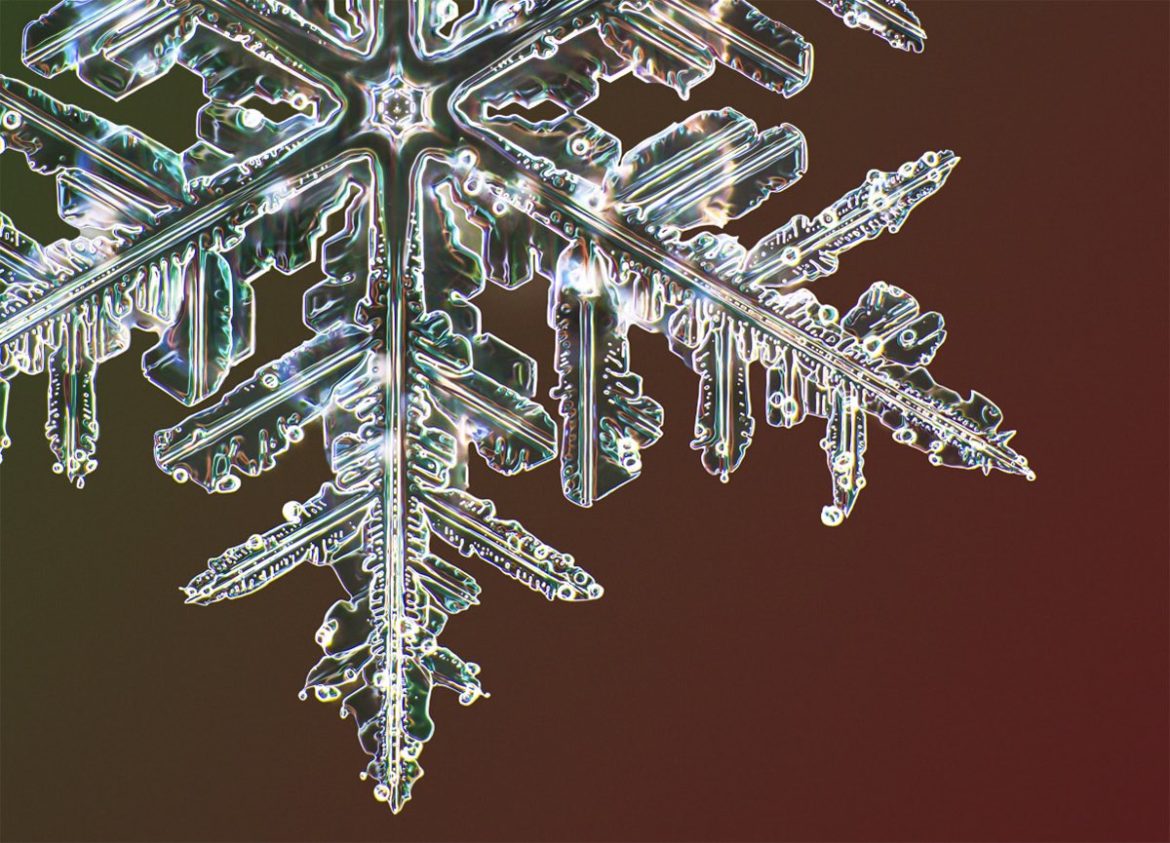

Photographer and scientist Nathan Myhrvold has developed a camera that captures snowflakes at a microscopic level never seen before

The following written content by Jennifer Nalewicki

The first chill of a winter storm is enough to send most people indoors, but not Nathan Myhrvold. The colder the weather, the better his chances are of capturing a microscopic photograph of a snowflake. Now, nearly two years in the making, Myhrvold has developed what he bills as the “highest resolution snowflake camera in the world.” Recently, he released a series of images taken using his invention, a prototype that captures snowflakes at a microscopic level never seen before.

Myhrvold, who holds a PhD in theoretical mathematics and physics from Princeton University and served as the Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft for 14 years, leaned on his background as a scientist to create the camera. He also tapped into his experience as a photographer, most notably as the founder of Modernist Cuisine, a food innovation lab known for its high-resolution photographs of various food stuffs published into a five-volume book of photography of the same name that focuses on the art and science of cooking.

Myhrvold first got the idea to photograph snowflakes 15 years ago after meeting Kenneth Libbrecht, a California Institute of Technology professor who happened to be studying the physics of snowflakes at the time.

“In the back of my mind, I thought I’d really like to take snowflake pictures,” Myhrvold says. “About two years ago, I thought it was a good time and decided to put together a state-of-the-art snowflake photography system…but it was a lot harder than I thought.”

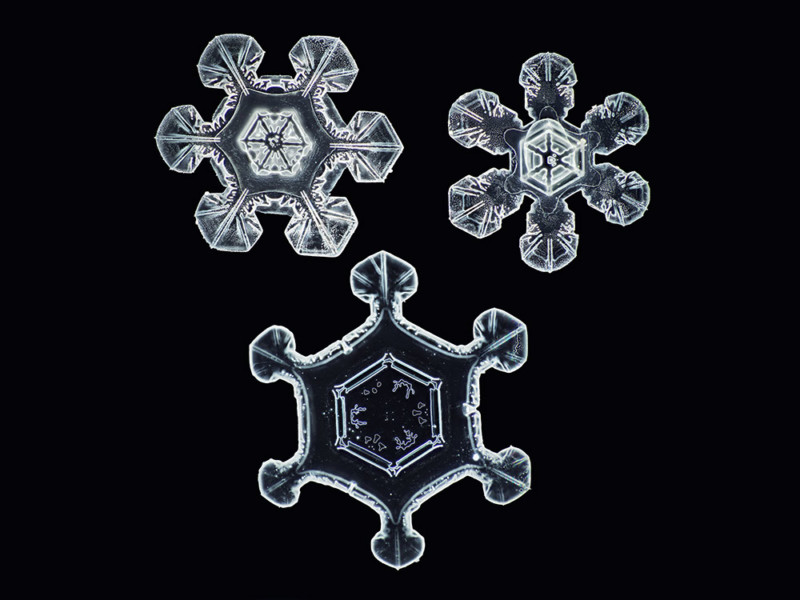

Photographing snowflakes is nothing new. In the late 1880s, a Vermont farmer by the name of Wilson Bentley began shooting snowflakes at a microscopic level on his farm. Today he’s considered a pioneer for his work, which is part of the Smithsonian Institution Archives. His photography is considered the inspiration for the common wisdom that “no two snowflakes are alike.” Read more from Smithsonian Magazine.

Advertisement