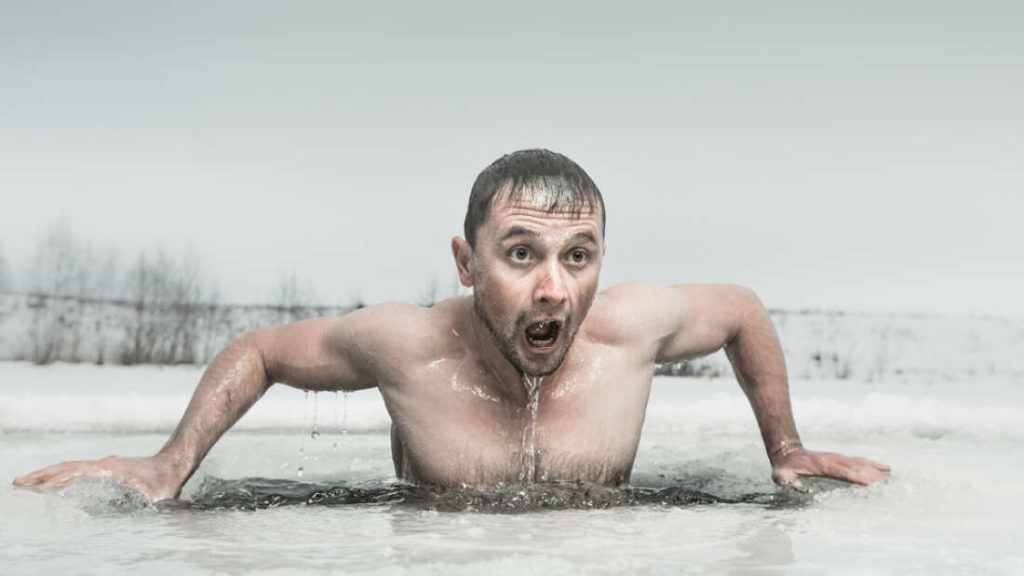

After years of anecdotal evidence, scientists have finally nailed down one link between brain health and the “polar bear plunge.”

Written content from Hanna Sparks

In a study of the blood profiles of regular winter-time swimmers in London, Cambridge University researchers have identified a protein that was shown to slow the onset of dementia in mice — and even repair some of the damage brought on by the disease.

For decades, doctors have observed the healing and protective benefits of cold environments on certain ill patients but had yet to find any connection.

When they revealed the role of a particular protein — the RBM3 — in other mammals, such as bears, the pathology behind its healing power began falling into place.”

In a 2015 study published in the journal Nature, the Cambridge team discovered “cold-shock chemicals” during animal studies on healthy mice, mice with Alzheimer’s and others with prion, a neurodegenerative disease. They observed that when healthy mice were put into a hypothermic state — below 35 degrees Celsius — and then carefully rewarmed, they seemed to benefit from a natural boost of RBM3. Once fully reanimated, researchers found the ordinary mice had also healed neurons that were damaged by the initial shock.

Mice with Alzheimer’s and prion demonstrated neither effect.

But in another test, scientists instead artificially increased RBM3 levels in the sick mice, then repeated the “cold-shock” process. This time, the protein seemed to prevent vulnerable synapses — or cell connectors — from breaking, suggesting that RBM3 might shield the brain from the effects of dementia diseases.

Their findings hinted at an explanation as to why hibernating animals, who lose 20% to 30% of their synapses during the winter to preserve energy, are able to regenerate those neural connections upon awakening in the spring.

At the time, professor Giovanna Mallucci, who runs the UK Dementia Research Institute’s Center at Cambridge, confessed to BBC Radio 4 Today listeners that the breakthrough study may end there as few human subjects would willingly submit themselves to hypothermia.

Advertisement

There are many myths out there

Those few, however, heeded the call of science. Martin Pate, a swimmer at Parliament Hill Lido in London, an outdoor pool open year-round, got in touch with researchers, volunteering himself and a small group of swimmers from the center — after all, they were used to frigid temperatures.

Members of a Tai Chi group who practice near the pool were enlisted as a control group, and not submitted to cold temperatures.

As researchers suspected, many of the swimmers, recovering from core temperatures as low as 34 degrees Celsius, showed notably high levels of RBM3 compared with the Tai Chi group. Read more from NY Post

Read other health and wellness stories from News Without Politics

Subscribe to News Without Politics