How a computer hacker infiltrated a phone scam operation exposing fraudsters and their schemes

The following written content from Doug Shadel and Neil Wertheimer

A light rain fell and a cold gray mist hung over the street as Jim Browning arrived home from work. A middle-aged Irishman with a strong brogue, Jim is a software engineer at a midsize consulting firm, and on this workday, like most, there were few surprises. He shared a pleasant dinner with his wife, and when the dishes were cleared, he retreated to his office, shut the door, opened his computer and went undercover.

Jim Browning is not his real name. The alias is necessary to protect him and his family from criminals and law enforcement, as what he does in the privacy of his office may be morally upright but technically illegal. It’s a classic gray area in the netherworld of computer hacking, as we will explain. What is important to know is that back in 2014, it was the same annoying robocalls that you and I get most days that set Jim on his journey to become a vigilante.

A relative of Jim’s had told him about warnings popping up on his computer, and Jim, too, was besieged with recorded calls saying his computer was on the verge of meltdown, and that to prevent it he should call immediately. As a software expert, Jim knew there was nothing wrong with his system, but the automated calls from “certified technicians” didn’t stop. One night that spring, his curiosity got the better of him. “It was part nosiness and part intellectual curiosity,” Jim said. “I’m a problem solver and I wanted to get to the bottom of what these people wanted.” So he returned one of the calls.

The person who answered asked if he could access Jim’s computer to diagnose the problem. Jim granted access, but he was ready; he had created a “virtual computer” within his computer, a walled-off digital domain that kept Jim’s personal information and key operations safe and secure. As he played along with the caller, Jim recorded the conversation and activity on his Trojan horse setup to find out what he was up to. It took mere moments to confirm his hunch: It was a scam.

Intrigued by the experience, Jim started spending his evenings getting telephone scammers online, playing the dupe, recording the interactions and then posting videos of the encounters on YouTube. It became, if not a second career, an avocation—after-dinner entertainment exposing “tech support” scammers who try to scare us into paying for unnecessary repairs.

“Listening to them at first, honestly, made me sick, because I realized right away all they wanted to do was steal money,” Jim would later tell me. “It doesn’t matter if you are 95 or 15, they will say whatever they need to say to get as much money out of you as possible.” Jim saw, for example, how the callers used psychology to put targets at ease. “They say reassuring phrases like ‘Take your time, sir,’ or ‘Do you want to get a glass of water?’ And they will also try to endear themselves to older people, saying things like ‘You sound like my grandmother,’ or ‘You don’t sound your age—you sound 20 years younger.’ “

Jim’s YouTube videos garnered mild interest — a couple thousand views at best. For Jim, this didn’t matter. The engineer in him enjoyed solving the maze. At the least, he was wasting the scammers’ time. At best, his videos maybe helped prevent some cases of fraud.

Then one day in 2018, Jim’s evening forays took an unexpected turn. A tech support scammer called from India and went through the normal spiel, but then he asked Jim to do something unusual: to log in to the scammer’s computer using a remote-access software program called TeamViewer. Later on, Jim found out why: The developers of TeamViewer had discovered that criminals in India were abusing their software, so they temporarily banned its use from computers initiating connections from India. But there was a loophole: It didn’t stop scammers from asking U.S. and U.K. consumers like Jim to initiate access into computers in India.

“They will say whatever they need to say to get as much money out of you as possible.”— Jim Browning

Hence, the scammer’s request. The voice on the phone talked Jim through the connection process, then told him to initiate a “switch sides” function so the caller could “be in charge” and look through Jim’s computer.

Presented with this opportunity, Jim acted quickly. Instead of “switching sides,” he took control of the criminal’s computer and locked the scammer out of his own computer. Lo and behold, mild-mannered programmer Jim Browning had complete access to all of the scammer’s files and software. And he was able to see everything the scammer was frantically trying to do to regain control.

This bit of digital jujitsu changed everything. Over the next few months, Jim figured out ways to infiltrate the computers of almost every scammer who tried to victimize him. “My process worked on almost every remote access program out there, certainly the ones most popular with scammers, like TeamViewer, AnyDesk or FastSupport.” He also figured out how to secretly install software that recorded what the scammers were doing — without them even knowing it.

Suddenly, Jim was sitting on some powerful knowledge. But as Spider-Man was told, with great power comes great responsibility. Jim wondered, What should I do with what I’ve learned?

Scammers mock and make fun of victims

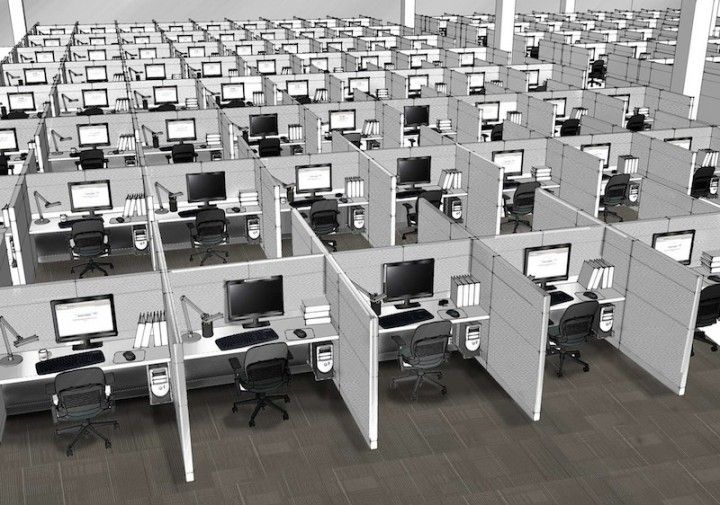

By now Jim had reverse engineered his way into dozens of scammers’ computers, sometimes four or five at a time. He would set his software to record, then leave for work as his computers did their thing. When he came home at night, he reviewed the footage. Often, he couldn’t believe what he saw: call after call of boiler room scammers — mostly in India — contacting older people — mostly in the U.S. and U.K. — and scaring them into spending money to fix a fake computer problem, or sending money based on other deceptions.

Jim posted these new videos, which gave an authentic, bird’s-eye view of how scammers operate. As a result, his YouTube channel jumped to tens of thousands of subscribers.

One night in May 2019, Jim found his way into the computer network of a large New Delhi boiler room. While lurking in their network, he noticed the company had installed closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras so the bosses could monitor their employees. So Jim hacked his way into that network and was able to turn the cameras this way and that, capturing the facial expressions and attitudes of dozens of scammers in action.

In one remarkable scene, he called one of the scammers in the boiler room and focused a CCTV camera on him as they talked. Zooming in, Jim could see that while the scammer was supposedly diagnosing his computer, he was actually playing Pac-Man. Jim got annoyed by this criminal’s nonchalance; call it hacker’s pride. So he decided to grill him.

“Where are you calling from?” Jim asked.

“San Jose,” replied the scammer from his desk in New Delhi.

“What is your favorite restaurant in San Jose?” Jim asked. The scammer paused and replied, “Why do you want to know that?” Jim then asked him, “Can you even name one restaurant in San Jose, California, without looking it up on Google?” The man became flustered and eventually hung up.

Jim continued to monitor the room in the following weeks, recording one tragic story after another of vulnerable people being exploited. One woman said, “I’m a nervous wreck. I have MS and I can’t understand a lot, but I’m listening.…” The scammer said, “That is the reason you are telling me you won’t live past next year, right?” She said, “Probably not. I’m a diabetic and I’m legally blind.…”

“Relax. You are in safe hands,” he said.

Another older man started crying when told it would cost about $1,500 to repair his machine. “Oh, bloody hell. I’m going to have a heart attack. I feel sick.” When the scammer asked why he was crying, he said he suffered from depression. As the man wept, Jim captured images of the salesmen in the room who were listening to the call, and laughing and pointing fingers mockingly at the victim.

This is when Jim reached a new stage in his journey: outright fury. He wanted to do more than make a few salesmen squirm. He wanted to stop as many operations as possible so they couldn’t continue to abuse people.

But Jim was careful; he had his and his family’s welfare to worry about. “I could have physically destroyed their computers by placing a virus in them, but I intentionally didn’t do that because there was really nothing on their computers worth destroying,” he said. “And secondly, if I physically destroyed property, I would be overstepping the mark.” Translation: He, too, would be a criminal.

So what could he do? Jim had already started to intervene personally when he thought he could prevent a fraud from occurring, by calling the victim, the financial institution or anyone else he thought could halt the scam. So he tried a new tactic: using “call flooding” software to tie up the boiler room’s phone lines with thousands of junk calls. Viewing the scene through his computer, he saw all the salesmen removing their headsets and complaining that the calls were nothing but annoying white noise. To his joy, he successfully shut the place down for several hours.

But then, reality set in: What Jim had done was just a trivial, temporary annoyance for just one operation. The next morning, the boiler room was back to business as usual.

Determined to make a difference, Jim moved to plan C: He contacted the media. He sent his best footage to the BBC, Britain’s largest news operation. And it bit, producing a half-hour program featuring the evidence he had gathered and naming “Jim Browning” as the source. It aired in the U.K. in March 2020, just as the coronavirus pandemic hit. The piece received widespread international exposure. Around the same time, Jim sent videos to local authorities in India; they arrested the scammers and shut down the boiler room.

After years of obscurity, Jim had become a YouTube star. As of this writing, Jim’s video of this particularly cruel boiler room has been viewed more than 14 million times, and his YouTube page has grown to over 2.8 million subscribers. Success!

And he had succeeded at walking the fine line. “Doing just enough to make life miserable and identifying who they are is probably the best thing that I can achieve,” Jim said.

But again, Jim asked himself, What now?

Finding a way to help victims

This is where I enter the story. i stumbled onto Jim’s YouTube page early in 2020, and after watching many of the videos, emailed him to see if I could learn more about his work. To my joy, he responded immediately, saying he would be happy to work with AARP on educating its members about tech-support scams. He said that while his videos do reach millions of people, most of his subscribers are male and younger than 40, meaning many are likely tech geeks, law enforcement or even scammers. He has found it difficult to reach older people who are the prime scam targets.

And so, in the middle of a pandemic, I entered into one of the most intriguing correspondences of my life. At first, I needed to verify his story. You already know that Jim Browning is not his real name; but for AARP to tell his story, we had to confirm his real identity and situation. Ultimately, he agreed, and I can assure you that the “Jim Browning” of this story is real and accurately described.

Once that was done, Jim and I spent countless hours over the summer looking over new footage he had recorded earlier in the day to watch phone marauders try to steal money. We communicated only on Skype, with our personal cameras turned off, again to protect Jim’s identity and his family’s privacy.

On four separate occasions, I witnessed a tech-support crime occurring in real time. The first time this happened, Jim was showing me what I thought was a recording from earlier in the day. I asked him when it happened, and to my surprise he said, “It’s happening right now.”

“Well, what do we do?” I asked, my blood pressure surging. “We can’t just let this transaction go through. They are about to send the scammer $10,000!”

Jim, an old pro at these situations by now, was already at work to find the victim’s phone number. Often, he could get it directly from the scammer’s computer; as we became more familiar, he sometimes would ask if I could access the person’s contact information through a U.S. public data aggregator service to which I subscribe.

In those cases, I would give Jim the victims’ phone numbers as fast as I could find them, and he would call to warn them. After initial skepticism, they typically became convinced that it was a scam, and decided not to send cash. Which is what many scammers actually asked for.

The picture below is of a woman holding a box with $10,000 in cash. The scammers turned her computer camera on and asked her to show them the package to prove she was really going to send it to them. In this case, Jim was able to contact FedEx, which intercepted the package and stopped delivery. Read more from AARP