How can we take pictures of Earth-like exoplanets? Use the sun!

“If we ever want to take pictures of a distant world like this, we need to think bigger.“

The following written content by Paul Sutter

Even the biggest telescopes on Earth can’t come close to resolving the nearest known Earth-like exoplanet to us, Proxima b. If we ever want to take pictures of a distant world like this, we need to think bigger.

One way would be to use the sun. The gravity of the sun bends space around it, and that bending is capable of deflecting the path of light. At just the right distance, the sun could act as a giant magnifying lens, providing the resolving power needed to image an exoplanet.

So how could we get a telescope to the incredibly distant spot where it could do that? A team of astronomers has proposed using an enormous light sail to propel spacecraft there.

Exoplanet dreams

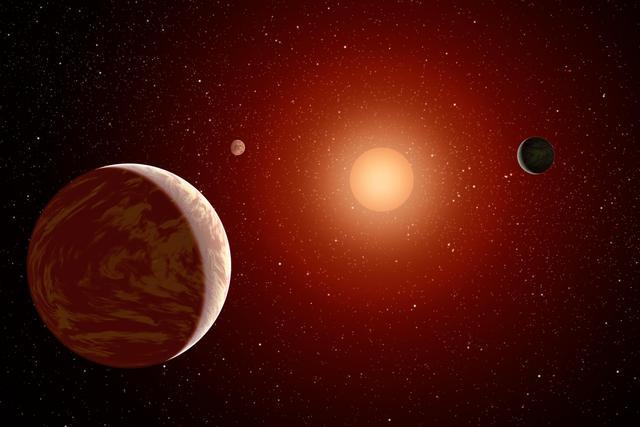

Astronomers are searching for an Earth-like planet around a sun-like star, at just the right distance so that liquid water can exist on its surface. To date, we have not found that Goldilocks planet, despite amassing an impressive collection of over 4,000 known exoplanets.

The vast majority of exoplanet hunting relies on observing very small, very distant objects. Usually, astronomers have no more than a single pixel’s worth of data to work with, and they watch for brightness variations or changes in the light’s spectrum to determine the existence of an exoplanet.

In a few rare cases, astronomers have been able to snap pictures of exoplanets, but those have been very special cases — nearby, absolutely massive planets.

Even if we were to find an Earth 2.0, we wouldn’t be able to take a picture of it. As an example, the largest optical telescope will soon be the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, with an aperture of 8.4 meters (27.6 feet). That’s a truly giant telescope. But if we were to point it at Proxima b — the nearest known exoplanet of any kind, at about 4 light-years away — at that distance, it would have a resolving power of 1.2 million miles (1.9 million kilometers), which is about 150 times the width of Earth.

Other upcoming telescopes, like the Extremely Large Telescope in Chile and the Thirty Meter Telescope in Hawaii, won’t be able to make much of a dent in that number. All of our planned observatories, both space- and ground-based, for decades to come, will never be able to see an alien planet as anything more than a single pixel of light.

Subscribe here

Bending gravity

Let’s say that one day we do confirm the existence of an Earth 2.0; we find a habitable world, and through spectroscopy, we determine that life may have found a foothold. How could we possibly take a picture of it?

The answer lies in gravity. Einstein’s theory of general relativity tells us that matter and energy bend space-time around them. Light is forced to follow this bending of space; wherever space bends, light must follow.

It was this deflection of light that British astrophysicist Sir Arthur Eddington used to perform the first experimental test of general relativity, when he examined the deflection of stars whose light grazed the surface of the sun during a solar eclipse. Due to the bending of space, the star appeared in the wrong part of the sky, by a distance perfectly predicted by Einstein’s equations.

Massive objects act like a lens. And lenses don’t just focus light; they magnify it. If you were to imagine the sun were a giant magnifying glass, all you would have to do is place a spacecraft at the focal point of that lens to take advantage of all that magnifying power. Read more from Space.