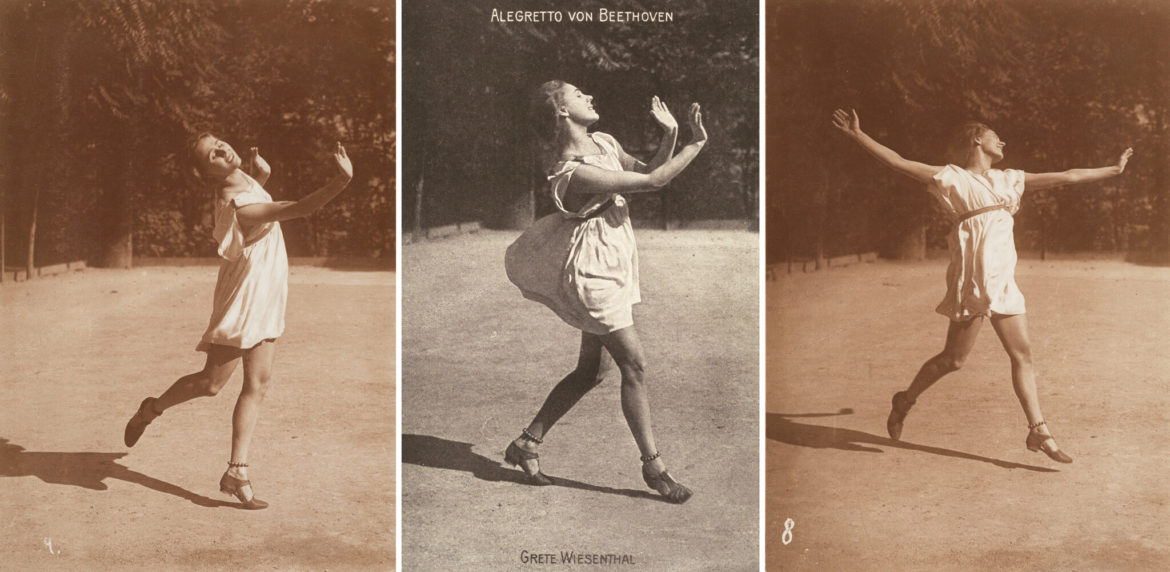

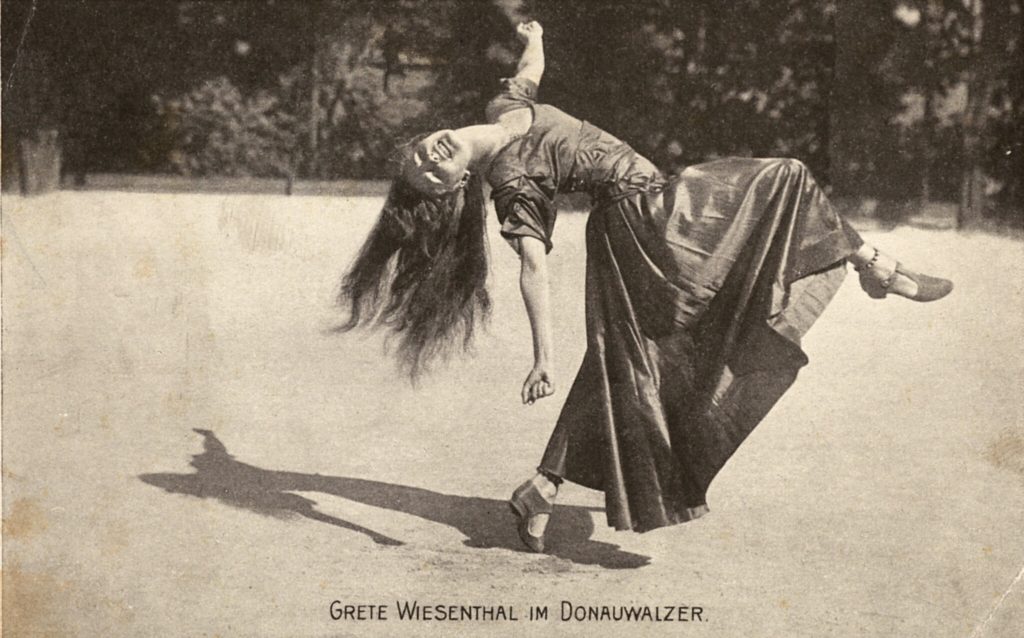

Dancing by herself, Grete Wiesenthal, a ballet-trained Viennese dancer, made the waltz modern and a vehicle for solo expression.

The following written content by Meryl Cates

Waltzing can go on for hours in an endless rotation, as partners coiled in each other’s arms whisk around a brimming dance floor. It requires a significant amount of physical contact, which is why the waltz was considered somewhat of a guilty pleasure until the early 19th century, when its popularity finally overthrew propriety. And now during the coronavirus pandemic close partner dancing raises eyebrows again.

In Vienna, the home of the waltz, a wave of cancellations has shut down the annual ball season. Usually, in January and February, hundreds of luxurious celebrations are held across the city, including a New Year’s Eve ball, the Hofburg Silvesterball, at the Imperial Palace. Just after this year’s events wrapped, lockdowns began. Planning for a new season’s programs came to a halt.

The waltz may have a reputation as the ultimate social dance for partners — the way it is traditionally performed at the balls — but there is another interpretation, one that resonates in this pandemic year of physical distancing. More than a century ago, the Viennese dancer Grete Wiesenthal transformed the waltz into a powerful form of solo movement.

When Wiesenthal first performed her choreography, with its swirling, euphoric movement and suspended arches of the body, she became a champion of free dance in Vienna and a cultural force in the city’s highest artistic circles.

Though her name is not usually found among the internationally renowned pioneers of modern dance, like Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Loie Fuller, Wiesenthal is revered in Austria, where her dances have been revived periodically since her death 50 years ago.

Like many Viennese, Wiesenthal, who was born in 1885, grew up with the waltz but her training was in classical ballet. She refined her technique at the school of the Vienna Court Opera, where, she would later insist, there was no focus on artistry.

A solo style of waltzing was Wiesenthal’s answer to what she considered ballet’s weakening relationship to music. She saw the art form, and the Opera’s productions, as hopelessly committed to uniformity, with no space for dancers’ self-expression. Read more from The New York Times.

For your interest:

Here’s another performance of the waltz from Dancing with the Stars, not solo: